Notes by Todd Monge

We decided to take a chance, save some money, and travel by mini-bus rather than in a full coach. It was a risk, but one I was prepared to take. Mini-buses, in Egypt traveled between set destinations, dropping passengers along the way, at times picking up others along the road. But while the destinations were fixed, their time of departure was not. Departure time, for an Egyptian mini-bus, is the moment it has a full compliment of passengers, and not a moment before. On a well established route, this is a positive, as the constant flow of passengers quickly fills the bus and departure is swift. The trip to Suez from Cairo was only an hour, and as we filled the last two seats in the mini-bus, we arrived in Suez well before noon.

We were dropped off in a fenced compound, filled with a countless number of mini-buses exactly like the one we had just traveled in. As we shouldered our packs, we walked to the nearest mini-bus, and said simply “Dahab!” The driver pointed off in one direction, and we followed his instructions, repeating the question. We eventually made our way to the rear of the compound where three rusty mini-buses sat in dejected silence, one totally deserted, the others with their drivers snoozing on the front bench. “Dahab?” we asked for the last time, and a young boy reached for our packs and tossed them up to the roof where he began to tie them down.

“How long until we leave,” Brian asked the kid. He didn’t answer. Brian walked over to the front of the bus and poked the driver. The driver jumped in surprise and grunted. “How long?”

“Half an hour, maybe hour,” he said and went back to sleep.

The doors to the bus were open, and three men sat patiently inside, waiting for the bus to fill and leave. “I want a good seat,” Brian said, climbing in the bus to secure his place and wait. I climbed in at sat next to him, hoping to be able to sleep a bit after spending the night on the train. An hour passed, I was unable to sleep, and not another passenger had arrived.

The mini-buses were all small Nissan mini-vans, with three rows of bench seats installed in the back. Including the front bench seat where the driver sat, in a van that would have a five person passenger rating, each mini-bus could hold 16 people, most uncomfortably. Each bench was squeezed in, so as people crammed their way into the mini-bus, you were contorted into a position that was impossible to adjust until the bus was stopped and your neighbor extricated himself from the vehicle. The pain grew to unbearable levels, but just when you though you were going to snap and demand that the driver leave you stranded in the middle of the desert, your body would go numb. It was impossible to complain because, for the people sardined around you, this was their daily mode of transportation, this was the best way to travel. At least they were cheap.

In optimal conditions, Brian’s patience level was no more than an hour. Sitting in the back of a stuffy mini-bus, legs crammed up to his chest, as the temperature steadily rose in the growing heat of the afternoon, were not optimal conditions. I was therefore surprised, that Brian lasted an hour and a half before loosing his temper. Brian suddenly jerked to his feet, lurched out of the truck, and dropped to the ground. He knew enough to not argue with the driver, aware that nothing could persuade him to leave until the van was full. “I’m going to look for another bus,” Brian asked, and tromped off, yelling to the individual drivers as he passed their mini-vans.

An hour later he had returned, holding a falafel and a bottle of water. He handed them to me in the truck and I thanked him and began eating. “No Luck?” I said, mouth full.

“No one going to the Sinai right now. Maybe later. Anyone else show up?”

“Three people, but that still leaves us needing five.”

Brian looked around. “Is Teeth coming with us?”

“Who?”

“Teeth.” Brian started to giggle.

One of the three men who had just arrived swiveled in the seat before me. He was a grizzled old Egyptian, wearing long flowing robes, more elaborate than a galybia, with a dusty white turban on his head. He had a graying moustache over his mouth, the lips of which were pouty and full. He spoke in Arabic to someone leaning on a neighboring van. As he spoke, his lips flapped around a mouth full of the most bent, twisted, rotting, teeth I had ever seen. Half of his teeth were gone, either entirely or rotted down to mere blackened stumps. The rest stood askew, jutting from his gums at seemingly impossible angles. Looking at the twisted mess, it looked as if closing his mouth would have been a physiological impossibility. As he fell silent, his mouth shut, and two of his teeth, one on top and the other on the bottom protruded the slit of his lips, pointing horizontally out of his mouth rather than stand vertically.

I laughed, and at the sound he turned his head and looked at me. I stifled my laugh and smiled, and rather than return the gesture, nodded and turned his back on me. “Yes,” I said, “I think teeth is coming with us.”

Brian climbed in and the wait began anew.

Two more hours passed before the revolt. The revolt began as grumbling, growled curses and mutterings between Teeth and his comrades. What began as low plaintive grumbling grew into loud bickering and open hostility flung at the driver. The curses became shouts, and as one the passengers rose, began to collect their belongings and stormed off the mini-bus.

“What do we do?” Brian said confused. All of the argument had been in Arabic, and the best we could do was infer the meaning of the curses. It was surprisingly easy to do, primarily because the tone of the voices and the non-verbals were universal and transcended the language barrier.

“I think it’s a revolt,” I said.

“Let’s join!” Brian said invigorated, thrilled to be participating in any action against the driver who had already wasted four and a half hours of our time. We grabbed our things and followed the other passengers.

The driver, seeing his customers deserting him, flung his body into their midst, barring escape, imploring them to stay. The argument raged, but the driver was able to calm the passengers, knowing in part that the gambit had been a bluff. Reassured that departure was imminent, the passengers again boarded the bus, growling to each other as the driver climbed to the roof to secure the luggage. It took him an hour to do so, stalling in the hopes of finding three more passengers. It worked, in part, and as the sun set we left Suez behind.

We didn’t make it to Dahab that night. Instead, after an interminable drive across the northern Sinai, stopping to drop passengers in the border town of Taba, Brian and I decided to get dropped off at the tiny seaside town of Terrabin. As the mini-bus drove off, Teeth grinning madly in the dim glow cast by the interior dome light, we looked down towards the beach. The last sliver of moon shone, casting a silver, glittery path across the Red Sea. It the distance, the mountains of Saudi Arabia loomed, dark and foreboding, forbidden to infidels like Brian and I.

“Want to convert?” Brian asked, looking across the water, knowing that his best chance of being allowed to enter Saudi Arabia was converting to Islam. “I’m thinking about it,” I replied seriously.

“I’d like to go on Hajj one day,” Brian said wistfully.

We walked down to the seaside, the smell of the ocean pungent, welcome after long hot days in the desert. It was nearly midnight when we staggered into the lights of the town. The settlement was small, mostly geared towards young Israeli soldiers, away on leave, eager to smoke hash and lie on the beach. In Terrabin there was nothing to do except lie in the sun, get stoned, and eat occasionally. In Terrabin, you could pass days without sleeping, so fully relaxed and rested, that sleep seemed unnecessary. The town was nearly deserted, occupied only by those whose goal it was to do nothing. After nearly being awake for nearly two days, traveling constantly, doing nothing sounded very attractive. We found a hut on the beach, with a mattress on the ground, paid the owner a dollar, and either slept or lay inert for two days.

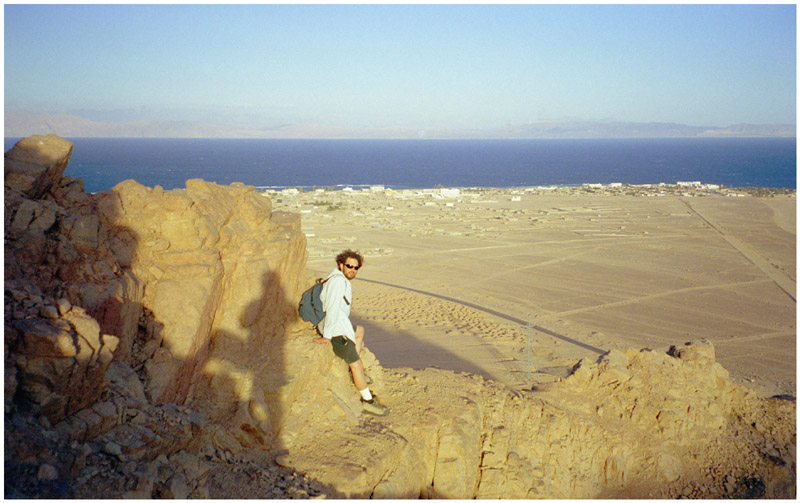

When our interest in doing nothing waned, we slid down the coast from Terrabin to Dahab. Dahab was a town on the cusp of explosion. It was currently a haven for backpackers, offering a multitude of cheap dingy rooms, with shared toilets. One didn’t mind the cellblock rooms, each with little more than a mattress raised off the floor. The rooms were for sleeping only, every waking moment of the day spent either diving in the ocean or basking in the sun on the beach.

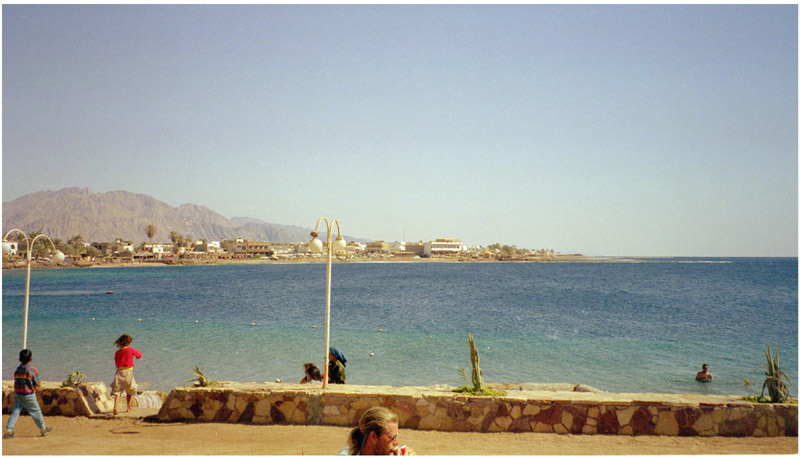

Dahab fronts the Red Sea at a gorgeous curl of a bay; it’s cafes and hostels fronting the azure sea. Palm trees grow along the shore, and in their shade travelers lounge and watch the day slip by. Bedouins roam the outskirts of town, offering camel rides into the desert. If you were clandestine enough they would sell you hashish or pot, which, with discretion you could smoke on the waterfront or in a quiet spot in a café. Dahab was a spot where travelers tended to get stuck, not wanting to leave the cheap drugs, lodging, and food. Drugs weren’t the main attraction in Dahab, but they were both cheaper and more readily available than Alcohol. Once travelers started partaking in the drugs, their desire to leave disappeared as fast as their sobriety.

Dahab had the feeling of a town in peril; a town about to be smothered by development, development that would wipe out everything that had made this sleepy desert seaside town so attractive. When the high rise hotels moved in, as they were soon sure to begin doing, the Bedouins would disappear back into the parched hills, moving up the coast, probably to Terrabin. Towns like Dahab had an alluring atmosphere. Possessing more than beauty, the entire essence of the town was captivating. The inviting ocean and all it possessed, the intrigue of the Bedouins, the pervasive freedom with drugs, and a lifestyle that required you to do nothing more than sit and stare across the ocean at the hills of Saudi Arabia, instilled a desire to stop wandering and become sedentary. But Dahab had a feeling, like the second to the last day of a week long vacation, of an inevitable, inescapable harsh return to reality. As wonderful as Dahab was, it gave you an unsettled feeling. I knew that one day I would want to return, to sleep again on the beaches and float over the beautiful reefs below. But I also knew that I could never come back. To do so would invite heartache; a nostalgic remembrance of what Dahab had once been before the inevitable over development. I had to enjoy that memory, cherish it, and never return.